Abdulrahman Zeitoun of New Orleans writes about his experiences rescuing storm victims, and about his arrest and ordeal on suspicion of terrorism and looting:

My name is Abdulrahman Zeitoun. I am the owner of Zeitoun A. Painting Contractors LLC, and Zeitoun Rentals LLC. I have been in business in New Orleans for almost 12 years. I have a very good reputation through out the City of New Orleans, and I am listed with the Better Business Bureau.

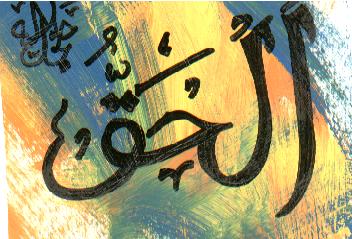

I am originally from Syria, and I came to the United States in 1973. I started my life from scratch, and worked my way up to where I am now. I am married to Kathryn M. Richmond, I have 3 daughters and a son with her.

Saturday - August 27, 2005

My wife and kids evacuated from New Orleans due to hurricane Katrina and headed to Baton Rouge. I decided to stay behind to try and minimize any damage that may happen to my property.

Sunday . August 28, 2005

Day 1

By Sunday evening, I lost my electricity and my roof started leaking due to the strong winds and heavy rain.. It seemed like it was raining as much inside my house as it was outside. I quickly went to the kitchen and got as many pots and pans as I could get. I put them under the leaks to contain the damage to the hardwood floors. I dumped water out of those pots and pans all through the night, and didn't stop until Monday afternoon. All I could think of was, man, had I not been here, those floors would have been ruined.

Monday . August 29, 2005

Day 2

The rain finally stopped falling. I looked outside my door and saw that we had a couple of feet of water in the street, and a few trees were down. I went on top of my roof, and saw that Katrina caused roof damage to my sun room and a few other areas on my house. I tried to temporarily patch them as best as I could just incase, it was to rain again. Anyway, after that, I took my canoe and went around the block to see what kind of damage my block had. I greeted a neighbor with his family, saw that more trees were uprooted, and a few power lines were down. I circled the block, then went back home. I spoke to my wife a couple of times on my cell phone, and told her that it was safe to come back. I was very exhausted from constantly draining the water out of the pots and pans, so I turned in for the night and went to sleep.

Tuesday . August 30, 2005

Day 3

I heard a strange noise coming from outside when I woke up so, I went to see what it was. When I looked outside, I saw the water passing in the street . It was moving so very fast, just like a rapid river. It was moving all around my house, and it looked like it was steadily rising. My first thought was the levee had broken. All I could think of was what to do next.

Should I move my vehicles? No, it was too late for that, so I quickly went inside and started bringing things upstairs as fast as I could, like food, water, any necessities. Then, I emptied all of the closets on to the kids beds upstairs and stacked all of the drawers on top of the dressers. I moved some of the kitchen stuff into the upstairs closets, and all of the books on the book shelf up to about 5 feet on top of my daughters' bookshelves and dressers. Then, I stacked the mattresses on top of chairs and end tables, the dining room chairs on top of the dining room table, and one sofa on top of the other.

My wife called and confirmed that the levee did break and to get out of there. I thought if I stayed there, I might be able to take care of my other properties, or even help people if they needed help. The only thing I could do next was wait. The water was moving too fast to go out in my canoe, so I went back inside my house and waited. By evening time, it was too hot and humid to sleep. I tried to call my wife, unfortunately, I couldn't because the cell phone battery died and the house phone wasn't working.

Wednesday . August 31, 2005

Day 4

The water was still rising when I woke up, it was now in my house. Around afternoon, the water finally stopped rising, so I took my canoe, and went out. I saw the same neighbor with his wife and children out on their porch. I asked him if he needed any help. He asked me if I would take him to see his truck on FontaineBleau Dr where he had it parked on the median.

I told him I was going to look at my properties on Claiborne so I wouldn't be able to come right back. He said he didn't mind then he climbed in my canoe and we started up Vincennes Pl. We reached the place on Fontainebleau Dr. where he had his truck parked. It was submerged. We continued up Nashville where we saw an elderly woman and her husband calling out to us for help. I told them I was afraid to put them in the canoe. It was small and might flip over and that we would go look for help and come back for them.

My neighbor and I continued heading up Nashville Ave. until we heard this muffled scream coming from somewhere. We couldn't find where it was coming from. I think the only reason we heard it was because the streets were so quiet. We yelled out to it. Asking "Where are You?" The muffled voice was found coming from a house on Nashville Ave. I hopped out the canoe and swam to the door. I tried to open it, but it was stuck. The lady inside kept yelling "Please help me!" "Please help me!" I kicked her door and finally got it open.

I found this old lady in a one story house, floating on her back, holding on to a piece of furniture calling for help. I told her I came to help her. She said she can't swim. I grabbed hold of her and tried to pull her out of the house. She was a heavy set woman, so it was very hard. When I got her out of her house, I told her to hang on to her porch railing. She said "Please don't leave me, Please don't leave me." I told her ," I can't put you in the canoe, it might flip," I promised her that we would be back with help. She yelled " I can't hold on very long. Please hurry, please hurry!"

I got back in my canoe and we continued up Nashville to look for help. As much as I was happy to have this little canoe, was as much as I hated that it was so small.We found many rescue boats going back and forth from Medical Memorial Hospital towards Jefferson Hwy. We tried to get them to stop. No one would. We called for them, begging for help. Not one of them stopped for us!Three men on one boat finally did stop and asked us if we needed help. I took him to where the lady was. She was still holding on to her porch railing. We tried to get her on the boat. She exclaimed she is a diabetic and couldn't use her feet, and we couldn't lift her cause she was too heavy. Then someone suggested that we use a ladder. The lady said that she had one by her garage. One of the men on the boat swam and got the ladder. Then we realized it wouldn't do any good because she couldn't climb.

One of the men suggested that maybe if we use the ladder as a stretcher, we could lift her up and put her on the boat. That was a great idea. With all of our might, and with much difficulty, we tried and succeeded to get her on the boat. On our way to pick up the first couple we met, we heard people calling for help. We searched for them all over until we finally found them on a little side street between Nashville and Octavia. We went to them and saw that there was an elderly couple. We picked them up and put them on the boat. Then we went to the first elderly couple we met.While we were getting the elderly lady on the boat, she told us that she has a canoe, and we could have it if we need it. We said our thank you's, and goodbyes - then the men took the people to safety.

My neighbor tied the lady's canoe to my canoe. I dropped him off at his home with the canoe, then I went home. I think he left with his family, cause I didn't see him or his family after that. After a little while I took off to my properties on S. Claiborne Ave. I saw that a few of my tenants, and neighbors stayed behind as well. I saw that the downstairs tenant was going into the upstairs tenants apartments. I asked him what he was doing there, he said he had permission. He tried to salvage some of his things by storing them upstairs. I asked him if the phone was working, and he said that it was. So I called my wife. She told me she was very unhappy in Baton Rouge, and wanted to go to her friends house in Arizona. I told her to enroll the kids in school as soon as possible because, we had no idea when they would be coming home.

While I was there, I found my neighbors German shepherd. We put her on the porch of the upstairs apartment and fed her. After this, I went home. It was very dark at night since there were no street lights. Thank God I made it safely. Other than a few barking dogs, the neighbor hood was pretty quiet.

Thursday . September 1, 2005

Day 5

As I was getting in the canoe to go to my houses on S. Claiborne Ave., I noticed that the dogs were still barking. I decided to look for them. I found them at the house diagonally across the street from my house. I knocked on the door. No one answered. I thought that perhaps the owner of the house might be upstairs because of the water. So I climbed the tree and got on to the balcony. The dogs were still barking inside the house. I knocked on the balcony door. No one answered. Then I walked around the balcony, looking in the windows. I did not see anyone. However, I did see 2 medium dogs in a cage with no food or water. I went back to the balcony door, pushed it open, and then took the cage outside on the balcony and let them out. They looked so skinny and weak. I went home to get some food and water for them. When I brought them the food, they were yelping, like a "gimmie, gimmie, gimmie" yelp. They scarfed that food down like there was no tomorrow. The poor things were making so much noise when they were eating, that the dogs next door started barking.

I went to the house next door to look for the other dogs, but there was no way to get in this house. So I found a large board that was floating in the yard next door. I took this board, and put it on the balcony on one house and on top of the carport on the other house. I walked across the board to the other side. I looked in the window, and saw 2 big dogs. They were in much better shape than the first 2 dogs I fed. I opened the window and called for the dogs. One of the dogs came to me, but the other one would run away when he saw me. I went home, got more food and water, and brought it to the dogs. The one dog woofed that food as fast as it could.The other dog refused to come and eat while I was there so I put food in the window for it, then I left.

I headed for S. Claiborne Ave. to call my wife. I saw my tenants from my house on the corner of Claiborne Ave. He said he wanted to leave. I brought him to a rescue station on St. Charles Ave and Napoleon Ave. I went back to my property on S. Claiborne and called my wife. She told me one of my neighbors from Vincennes Pl. called and asked if I could check out his house. After I finished my phone call, I headed back towards Dart St. I stopped at the mans house and accessed the damage. I saw that some of his trees were down, and the there was a lot of water in his house. He has a raised basement house and the water completely covered the basement section of his house and went up towards the windows on the second floor.I continued home. When I got there I got some food and water for the dogs, and fed them. Then, I went back home.

Friday . September 2, 2005

Day 6

Friday morning, I got up, went and fed the dogs, then headed towards S. Claiborne Ave. It was a windy day. it made it hard for me to row my little canoe. When I got there I called my wife, and my brother who was in Spain. They begged me to leave and then asked me how long I plan on staying there. I said as soon as I find out what is going to happen to our city. Meaning, if it was going to be a while for the water to leave the city, then I will leave. If it will only be a few days longer before the water goes down then I will stay. They asked me about food, I told them I had plenty. My wife did all of her shopping before she left for Baton Rouge. So my house was stocked with canned and frozen food.

While I was at this house, my neighbor from Dart St., who is a professors at Tulane called me and asked if I would check on his fraternity. He was in charge of this Fraternity and was worried about it. He wanted to know what the condition of it was. I finished using the phone, so I decided I would go and check on his fraternity on Burthe St. It seemed like the further I got out, the lower the water became. By the time I reached Burthe St., the water was about less than a foot deep. I saw that there were a few fallen trees, but the damage was not so bad in that area. I went inside the fraternity. I met up with an old friend. He was very happy to see me. He said that he had been there since the first day of the flood. I asked him if he wanted to come with me or stay there. He quickly decided to leave that place and go with me.

By the time we left there, the wind had gotten stronger. We turned back towards Claiborne Ave. When we got to my rental properties, I saw my neighbor who lived caddie-corner from my house. He asked me for help. He said he was out of his medication, and needed medical help. He had an elderly lady with him. She was taking care of him, but she needed medical help to. I told him, I would go and look for someone to bring him to safety. I promised him I would be back with help when I was leaving. He is a pastor, and he was in a wheel chair. He knew me for my word. He trusted me. I could not let him down.

I had a very hard time steering my canoe to the Memorial Medical Plaza. I finally made it. I tried to go inside. There was a lot of military men there. I told them about the pastor who needed help. They were very, very, cold, cruel and mean. They in a very ugly tone, told me they can't do anything for him, and I need to go St. Charles and Napoleon Ave. where the medical station was. I told them I can't go that far. The wind is making my canoe very difficult to steer my canoe. Not only that, it started sprinkling. I asked someone if they could come and get him. They are the military. With all of the technology they have, they could have called someone for this man. But THEY REFUSED! THEY REFUSED TO CALL FOR HELP FOR THIS MAN WHO WAS SICK AND IN A WHEEL CHAIR!

I felt like I had to do it myself. I had no choice. It took me a long time to get to St. Charles Ave and Napoleon Ave where the medical station was. But, I finally made it. When I got there, I saw many more military men. I spoke to someone, who told me to speak to someone else, who referred me to someone in charge. I gave him all of the information for the pastor. He told me he would get someone over there to the pastors house. The man in charge said he would. I believed him, cause he wrote the information down in his book. I left there and headed back to Claiborne Ave. and made a few phone calls. I saw at that time that my tenant had obtained a small motor boat. I asked him where he got it. He said someone gave it to him so he could help people in need of help. I thought, hey, that's great. As I was leaving, I thought I would check on the pastor to see if he and the lady had been picked up. That man was still sitting there since the time I left him. he was sitting in the rain on his porch, in his wheel chair waiting for me, because I said, I would bring him help. All those hours he waited. No one came for him. That doctor lied to me. I went and got my tenant because he had bigger boat than mine. We tried lifting the man and his wheel chair up. It was very hard, but with all 3 of us (me, my tenant, and old friend) we managed to lift the man, with great difficulty and put him in the small motor boat. He was yelling "Thank You! Thank You!" Then we helped the older lady in the boat as well. We asked him where he wanted to go. He said, anywhere that he could get help. We took them to the medical station on St Charles Ave, and Napoleon Ave. We left them at the medical station, and I took my friend to my house. When I went to give water and food to the dogs, I saw that one of the smaller dogs had been blown off the balcony by the wind. He was holding on to the tree branch with his teeth. I picked him up and put him back inside. I gave all of the dogs food and water, then went back home.

Saturday . September 3, 2005

Day 7

I made my usual rounds of feeding the dogs, and heading up to my properties on S. Claiborne Ave. Every time I would go to S. Claiborne I would take a different route. Hoping that I would be lucky enough to find someone in need of help. I mean, the feeling you get when you help someone is indescribable. This day, I took a really long route to S. Claiborne Ave. I went to FontaineBleau to Napoleon Ave, then from Napoleon Ave, to S. Claiborne. I found with box of water in the street, picked it up and put it in my boat. I also found a fog horn. Which I used when I would pass through neighborhoods. I would hope that someone would hear it and call out if they needed help.

When I arrived at my house on S. Claiborne Ave, I saw that the neighbor who left her German shepherd, came back for her. I invited everyone to my house to eat. The meat in the freezer had thawed out by now, and if I didn't cook it soon, it would have all been ruined. So everyone came to my house, and I started the barbecue grill on top of the flat roof at my house. My wife must have bought out the store. She had all kinds of meat in the freezer. We had lamb, beef, shrimp, fish, and a bunch of other stuff. I cooked enough food for 50 people. We ate all that our stomachs could hold. I gave everyone plates of food to take back with them, then I fed a lot of it to the dogs. By this time, it was all I had left to feed them anyway. Trust me, they didn't seem to mind. I saw a huge fire while I was on the roof. I got in my canoe and headed in the direction of the fire. I thought either my warehouse/office was on fire or it was one of the neighbors places. When I got there, I saw the entire block next to my office was on fire. There was a fire station just 2 blocks down. But no one was there to put out the fire. The staff must have re-located. The fire was out of control and there was nothing I could do so, I went back to my house on Dart Street.

Sunday . September 4, 2005

Day 8

When I got up, I went and fed the dogs, and gave them water. I went home and did a few things around the house, and then relaxed for the rest of the day. I did not venture out on this day.

Monday . September 5, 2005 .

Day 9

I got up early, gave water and food to the dogs, got in my canoe, and traveled to Claiborne. When we got there, I called my wife. She told me she was now in Arizona. I asked her if she enrolled the kids in school. She didn't have a chance at that time. She arrived in Arizona late Sunday afternoon, and Monday was labor Day so the schools were closed. We spoke for a while, then she said they might be forcing people out of the city by military force. I told her I feel like I am of some use here, but, if they tell me I have to leave then, I will. She also told me that a client of mine called and asked if I could go and check out their house on N. Hagen. I told her I would go tomorrow and look at it. She also asked me if I could find their cat. It went outside before the storm, and they couldn't find it before they left. I told her to tell them I would. I went back to Dart St, fed the dogs left over bar-b-que, then went home, ate, and relaxed. We really didn't get much sleep the past few days. There were many helicopters flying above our roof at a very short distance. They were very noisy.

Tuesday- September 6, 2005

Day 10

Tuesday morning, I fed the dogs, then headed to N. Hagen to my clients house. I passed my cousins house on Canal St., I didn't see his car, so I continued on to N. Hagen. On my way to N. Hagen, I saw a military boat with some journalist on it. They stopped an asked me questions, like why am I here, and who am I with. I told them I am here for anyone who needs me, and I work with everybody. Anyway, Some of the areas we traveled in had much water, other's had no water at all. In these areas we had to carry the canoe. It was very heavy for being so small. My friend accidentally dropped his side of the canoe. When he did this, my side somehow, twisted, and started hurting. When I got to N. Hagen, I looked for my client's cat. I couldn't find it. Then I started looking at the damage. I saw that he had a couple of feet of water in his house, and a couple of broken windows. After checking on my clients house on N. Hagen, I headed towards, S Claiborne Ave.

I saw a helicopter hovering in one spot for a few minutes. he was close to the ground. I didn't want to go close to the helicopter cause, every time I did, my canoe would spin around and almost flip over. So I waited for it to leave. When he left, I saw why they were hovering that area. They were marking the areas where the dead bodies were. This was the first time I saw dead bodies in our area. I went back to my house on Claiborne. As I walked up the stairs, I heard the phone ring. It was my wife. She was worried about me. It was unusual for me to go this long in the day without calling her. I told her about my clients house, and about the bodies I saw. She asked me if it was anyone we knew. I told her I didn't have the heart to look. After I spoke to my wife, I spoke to my brother in Spain. When I was finished, I tried the water to see if it was working. To my surprise, it was. I quickly took a shower. It felt so good to be clean. When I was finished, I told my friend that he should take a shower before the water runs out.

When I entered the area where the phone was, I saw a strange man there. I asked my tenant who he was, and what he was doing here. My tenant said that he was with the search and rescue team, and he needed to use the phone. I told him, "Oh, ok." We heard people outside. My tenant went to talk to them. It was the military. They asked him if we needed water. We told him no thank you, we have some. Then they jumped out the boat, went inside the house with their machine guns, and they were yelling at us to get in the boat. One of the military persons searched the house, for what? Only God knows. They treated us like hard criminals. They asked to see our ID cards, we showed it to them, they didn't even look at it. They only returned it to us. I told them I own this house, and my tenant was trying to prove to them that he lived there. They didn't care. They forced us out by gunpoint. We asked them where they were taking us. They said, "talk to my boss." We were taken to St. Charles Ave and Napoleon Ave. As soon as we got out of the boat, the military personnel jumped on us in a very rough manner, and handcuffed us. We were treated very, very badly. Then they put us in a white van. We asked the military who were they and why are they doing this to us. They said they were from Indiana, and they were only following orders, and doing their job.

They brought us to the bus station. We saw lots and lots of military personnel with many different types of weapons/guns. They made us sit down and wait to be as they called it "processed". They took our fingerprints, and photos. They had us under maximum security. We did not know what was going on. There were guards from Angola and New York prisons that were running the bus station like a prison camp. After processing us, they put us in a make shift chicken cage. Actually, it was the bus terminals that they turned into prison cells. It looked like a giant chicken cage. It was filthy dirty. They left us there for 3 days on this stinky, oily, filthy dirty floor. With no blankets or pillows. I swear, had we been in a prison in Afghanistan or Iraq, we would have been treated better. Somehow, I got a splinter the size of a tooth pick in my foot. It was the size of a tooth pick in width, and about half the length. It was getting infected, and caused me quite a bit of pain. I asked them if I could see a doctor. They refused me. Every day, I asked for a doctor. the splinter was lodged in my foot. I couldn't get it out. I saw a doctor helping other prisoners. I called out to him for help. He yelled at me in a very rude voice, that he was not a doctor. But he was a liar. He was a doctor. He was wearing green clothes, and he had a stethoscope. No one would help me.

On the third day I was in this hell hole, they fed us an MRE that came with a small glass bottle of Tabasco. I broke that bottle on that nasty floor, picked up a shard of glass, then cut my foot open where the splinter was. The skin had grown over the splinter. My foot was infected. So much puss came out. Very painfully, I managed to get the splinter out. I squeezed out as much pus as I could, and hoped for the best. We would ask the soldiers why we were here. One would say because of looting, another would say because of terrorism, and another would say something else. They were trying to stick us with whatever they could.Later that afternoon, they moved us to Hunt Correctional Center in St. Gabrielle. They so called "processed" us again. They filled out a paper on each of us. It was asking us if we had any allergies to food/medication. We told her that we do not eat pork. We are Muslim, and it is forbidden in our religion. She also asked us if we had any medical problems. I told her about the left side of my body. I was in a great deal of pain from it. I didn't even bother telling her about my foot. Would not have done me any good anyway. She wrote this down in my file.

They brought us to a maximum security section of the prison. I asked if I could use a phone to call my wife. They refused me. Flat-out told me no. They treated us like we were hardened criminals. They put 3 of us in a cell the size of my bathroom. The cell was only 8'x8'. They had on open toilet in the room. So, everyone would see me use the bathroom. There was no privacy on the toilet. The pain in my left side was hurting so much. I tried to control it as much as I could. I asked to see a doctor. I was refused. I continued to ask for a doctor. they told me I had to fill out a form. So I did. A week went by, and still no doctor. I asked where is the doctor. They said I need to fill out another form, because they lost the last one. This was all a bunch of bullsh*t to me. I was suffering. I was in so much pain, I had to grit my teeth to stop from screaming. I filled out another form, and turned it in. I continued to ask for a doctor. Since a doctor wouldn't come, I asked for a Tylenol. They said I need to see a doctor to get any medication. But I couldn't see a doctor cause not one of them would come to me. Another week went bye. Still no doctor. Within the first week, an individual from homeland security came to us and interviewed us. He asked me a lot of questions. Then he said, I was clean, and he had no interest in me, and never has had any interest in me, nor my friend. I kept asking for the phone. After about 2 weeks they said we could finally use the phone.

There were 50 people trying to use the phone. Each one of them was allowed 3-5 minutes only, and we were only able to use the phone in the late ours of the night. Bye the time it was my turn, I had fallen asleep. I must have dozed off waiting. They did not wake us. They simply went to the next cell. In the morning, I asked for my turn to use the phone. They said I missed it. I was really upset. I knew my wife was worried. I needed to find a way to contact her and let her know where I was. But everyone I begged/pleaded to call my wife, just told me no. I had to talk to her. Oh, my God I was in so much pain. Still no doctor came. The guard told me it takes up to 3 days after the doctor gets your form before he will see you. It has been over two weeks. Two weeks and we weren't even allowed to leave our cells. We ate, slept, and crapped in one room. We didn't see the light of day. Also, every meal they served us, had pork on it. I was unable to eat. I was very lucky when they didn't put pork on the grits. Otherwise, I starved. They served pork just about 2-3 times a day. They knew I couldn't eat this. So many days, I did starve.

The next night I stayed awake the whole night waiting to use the phone. By the time it was my turn, they cancelled the phone service to us. I did not know that. The guard came to me when he saw me awake in the late night/early morning and asked me why I was still awake. I told him I was waiting to use the phone. He said the time was finished. I asked him to please let me use the phone. He spoke with another guard, and they agreed to let me use the phone. I tried to call my wife, but cell phones do not accept collect calls from prison. I felt I lost all hope.The first court date I had, the public defender told me not to say a word. Just listen. The judge came out and set the bail to $75,000. he said I was being charged with looting, and possessions of stolen goods. I couldn't believe they were charging me with that. I didn't have anything on my possession except my wallet. Which they took. They were just trying to stick us with anything they could. Since the terrorist accusations didn't work, they were going to pin us as looters. This was a bunch of bull.

Also, $75,000. for a bond. They knew that no one could come up with that kind of money. No banks were open in New Orleans, and the city was upside down. I needed to get in touch with my wife so she could get the papers and prove that this was my house. The Judge told me, that he was not here to hear me. Only to set a bond. Even if we did have the money, there was no place to pay the bond. There was not one in existence at that time. There was no bond system for New Orleans prisoners at that time. I felt I was really being screwed.The next court date, my real lawyer was there. Someone must have called my wife. She had MY lawyer there. However, there was no court system set up, so not much could be done for me at that time. I was very disappointed again. He said he could try to get the bond lowered, and the only way to get out was to pay the bond, or put up property. Still, there was no place to pay any bond at that time.

Finally, on the third week I was there, they decided to improve our living conditions. They moved us to a minimum security level of the prison, and we were now allowed to go outside for a couple of hours a day. Still, no doctor looked at my side. Which left me moaning through out the night, and sometimes I could deal with the pain. Other times, I couldn't. I can't believe it. I constantly asked for medical treatment. They didn't give me any. What did I do to deserve this treatment? Why were they treating me like this? I truly feel in my heart that I was discriminated against. Why else would they arrest me?Finally, my wife was able to come to New Orleans. She dug through a collapsed building to get the property documents to help get me out. On Thursday she signed over our the warehouse as collateral for my bond. I still wasn't released that day. They made me wait till Friday. They made me stay a total of 23 days in that place. I feel sorry for my friends that are still in there under bogus charges.While I was being released, I asked for my wallet. The Hunt Correctional Center said they didn't have it. they said it was in New Orleans.

All I had on me for ID was a prison ID. I couldn't travel with this. When my cousin, and wife came to pick me up, they took me to his apartment, where my Aunt, Uncle, and cousin's wife were waiting for me with delicious food. After I showered, I ate, then I was taken to Our Lady Of the Lake Hospital. I lost 15 pounds while I was in prison due to the food they were trying to serve me.They did blood work, and X-rays on me. It was documented that I have a torn muscle. I still suffer from this till now. I have been seen by three real doctors and I am on medication. I suffer so much from this. I think it would not have gotten so bad had they let me see a doctor at least one of the 23 days they kept me in there.

On that following Monday, My wife and I went to the bus station where they kept me. I asked for my wallet. At first, they said they couldn't find it. Then they said they need it for evidence. My wife did not except this. They told her she needed to speak with the District Attorney. She saw Mr. Eddie Jordan there and asked him for the wallet. he refused to give it to her. So she went in and fussed a little. She told them that I couldn't travel with a prison ID. She said I was Arab, and they might think I was a terrorist. Finally someone went and got my ID, green card, social security card, and drivers license. They stole my wallet, and all of my credit cards. They either kept, stole, or lost, my wallet, visa card, master card, Lowe's, and home Depot cards, and a lot of business cards. Well, at least I got my Green card back, and my driver's license.You know, the sad thing about all of this is, those dogs, that I saved from starvation, died. I pleaded with the people who arrested us to please take care of the dogs. I gave him the address where they were. He wrote them down and said he would send someone to get them. HE LIED. Those dogs died. When my wife and I went back to our house on Dart St, we saw the owners of the dogs. I told them what happened and I asked about the dogs. They wondered why there was a board leading from their house to the other. They thanked me for taking care of their dogs, and then they told me they found them dead in the house. They also found the other 2 dogs from the neighbors house. They were dead too. All of this could have been avoided.

The tenants apartment had been looted after we were arrested. All of her Jewelry had been stolen, along with the downstairs tenants laptop computer and a few other items. All the trouble he went thru to save what little bit of stuff he did have, was all in vain. He saved it from the flood, but had it stolen by the looters after we were arrested. My family, neighbors, and friends call me a hero. The military that were in this city called me a terrorist. When that didn't stick, they switched it to looter. What a bunch of liars.My wife tried numerous times to reach me. They refused her all of her rights. She was not allowed to speak to me, visit me, or anything else. They said she had to speak with the District Attorney. She left many messages for them to call her back. Eddie Jordan never called her back. She fought for me to see a doctor. Yet no one ever came. She wasn't even allowed to see me at the trial/bond hearing. It was all done at the prison. No one was allowed to see me.

She was told to come to court for me, she even brought people with her. No one was allowed in. I wasn't even convicted of anything. Yet I was treated like I had killed someone. My rights were violated, and so were my wife's. It is suppose to be innocent until proven guilty. In my case it was guilty until proven innocent. My wife asked me if I was read the Miranda Rights. You know, they didn't even do that. I guess that is why they didn't give me any rights. If they didn't read me my rights, then, I guess, that means I didn't have any.